Publishing and presenting

As researchers, we have an obligation to share our discoveries with the academic community and with the general population. Research without the purpose of advancing further research and common knowledge is pointless. Many dread having to write a lot or to speak publicly. However, these are two core skills of a researcher, and during your Higher Degree by Research (HDR) journey you will learn how to most effectively apply these skills.

Research is defined as the creation of new knowledge and/or the use of existing knowledge in a new and creative way so as to generate new concepts, methodologies, inventions and understandings. This could include synthesis and analysis of previous research to the extent that it is new and creative. (Australian Research Council)

Click on the options below to learn more about either presenting at conferences or writing for academic purposes:

Conference presentations

Conferences provide an opportunity for you to meet like-minded people who are researching in related areas. In one place, you will see many different related research findings that may inspire and help you progress or refine your own research. In addition, conferences give you the opportunity to meet other researchers and start a professional network that may help you after your HDR journey has come to an end. Knowing where and how other researchers go about their interests can open doors for postdoctoral research fellow positions and other opportunities for your career development.

Publish or Perish!

One of the key measurements of academic success is your publication record. A publication record is the list of your journal or book publications as well the impact they have had on the research community. Remember that it is the task of researcher to contribute to the establishment of new knowledges to advance our understanding of the world. Publishing through journal articles, books or book chapters (and conferences) are all different ways of doing this. In addition, your publications contribute to your institution’s overall success – in particular, for receiving important funding. Hence, building your academic status is important for your standing within and outside of your current institution.

When deciding to go to a conference, you may need to consider which part of your research you would like to present. The amount of time you are given for an oral presentation or the size of the poster you want to present may be limiting factors for what you can present. You may also need to consider what other publishing options you have for your research. You may have found something very innovative and ground-breaking and will want to publish this in a sought-after high-impact journal – Would it be better then to also present this at a conference or do you prefer to have it all saved for the journal paper? You will need to discuss these options with your supervisor to make a decision. (More on publishing journal paper can be found in the section Publish or Perish!).

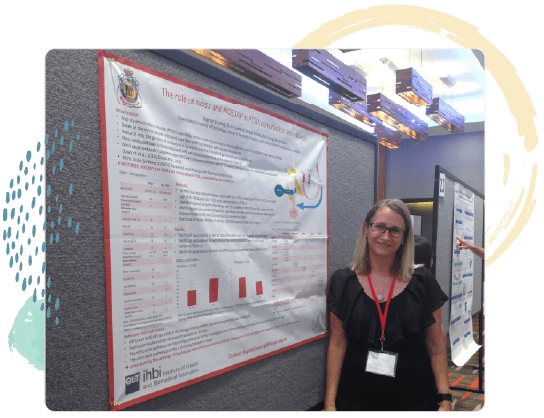

What is the general difference between a poster presentation and an oral presentation? For a poster, you will have to prepare a poster (usually A3 or similar sizing but always check with the conference organisers about the appropriate formatting) that shows in overview what you have found. See the cheat sheet area for helpful tips on how to prepare a poster. You will be allocated to a session, and during the session time it is expected that you are near your poster and can answer questions other interested researchers may have. This usually happens in a more personal approach as it is often you and one or two other people who will be chatting about your (and sometimes also their) research.

An oral presentation is when you have to prepare a powerpoint presentation and a talk. You will need to present your research within a given time frame (usually about 15 to 20 minutes) and be ready to answer questions from your audience (about another 10 minutes for questions). These sessions are formally moderated by another researcher, usually one quite senior in the field. Check the cheat sheet area to learn more about how to effectively prepare for such a presentation.

Your academic success is reflected in how frequently your work is cited and in which academic journals you have been able to publish. Academic journals are ranked on “impact factor”. The impact factor is calculated based on number of articles, the number of citations per article and the distribution of readership. Different sources for these calculations use slightly different measurements. Usually, the higher the impact factor of a journal, the more highly regarded the journal is in the research community. Each institution may use slightly different services for you to check for appropriate journals and their impact factors. Some examples of these services are Scopus, Web of Science, and Scimago jJournal and Country rank. So, ideally, you publish in high-ranking journals to reflect greater academic standing. Publishing in these journals will ensure that your work receives exposure in the academic world, hopefully attracting many citations in other articles. The more your work gets cited, the more it establishes your standing within a particular field of knowledge and will pave the way to establish your academic career through grant applications and for promotions.

Now that you understand why you need to publish, let’s focus on what you can publish and how it counts towards the academic standing of you and your organisation . Engage with the infographic below to gain an overview of the different options:

Journal Articles

Books & Book Chapters

Publication process:

When you prepare your work for publication, you will need to ensure that you are diligently preparing your work for the respective journal or book. There are often many detailed requirements of what you need to do in order to have your manuscript accepted. All journals publish formatting requirements for manuscripts on their websites and you will need to make sure that you are following them meticulously as otherwise your manuscript submission might not get accepted. Because journal articles are the most common form of publication, we will briefly go through the process of preparing your manuscript for a journal.

When you decide with your supervisor on the work you want to publish, you will need to write a manuscript that contains the following elements:

An overview of the current landscape leading to your research questions or hypothesis of the work you are presenting. The introduction needs to provide sufficient detail to “catch the reader up” to the context of your research. Have seminal (those papers or work that changed the way research is done or challenged knowledge in a profound way) and most current literature incorporated on your introduction. If you can, cite papers from the journal you want to publish in. You end your introduction with the aims of your work, which will be either a research question or your hypothesis. As with your thesis, they need to obviously flow out of your introduction.

The next section is the Methods section in which you need to concisely and correctly describe (all) the methods you used to collect your data. It is important to give sufficient detail so that other researchers can replicate your study.

After the Methods section you will present your results, ideally linking them back to your hypotheses. Make sure you illustrate and highlight important information by creating tables and figures. These will need to meet the formatting requirements of the journal, so ensure you are familiar with those.

The last section is the Discussion section. Here you critically reflect on your results and how they link to existing research, what your study contributed and where the limitations are. It is important to note that every piece of research work has limitations so there is no need to be overly critical, but you will need to honestly acknowledge what could be done differently or additionally to enhance this line of research in the future and to what extent your findings might be compromised by the limitations of your study.

If you will, a journal paper is like a mini-thesis about one particular part of your research work. You will need to be concise as many journals require a certain page or word limit so they can accommodate several researchers’ contributions in an issue of a journal. If you are unsure about your ability to write academically and concisely, use the cheat sheet and offerings through your institutions to gain more confidence in your academic writing. This will be an important skill in your future career.

Additional items you will need to prepare are the abstract, authors and their affiliations, the reference list and tables and figures, and any other elements that will be helpful for the reader to have to better understand your research. Most submissions also require you to write a brief cover letter outlining why the editor should consider your manuscript submission for publication.

Important

You will also need to format your manuscript according to the specifications of the journal you have picked. All journals have guidelines for authors that you should carefully study and adhere to when preparing your manuscript. Some journals will not accept your submission if you have not carefully prepared your submission.

Once you have submitted your finalised manuscript and it has been accepted as a submission by the editor, a peer-review process will occur. You might have heard about the dreaded “reviewer #2” who gives harsh feedback. This can happen but generally, the peer-review process is supportive and will help you enhance your manuscript for publication. Peer-reviewers are experts in the same or related fields and will look at your contribution with fresh eyes, providing invaluable insights into how your research is seen by people outside of your research group. They may discover important things that you and your team couldn’t see because you have been too involved in the details. You can see, that while academic critique can feel harsh at times, it does serve important purposes that will ultimately improve your research and writing significantly.

When you do receive your peer-review it is important to keep the perspective on how this feedback can improve your document. Try and address all feedback and be professional and exhaustive in your responses. Your peer-reviewers have invested time and effort in providing you feedback so make sure you treat it with respect. Also keep in mind that once you have started publishing you may be asked to become a peer reviewer as well. Try to think about how you would like your feedback to be treated after you have put time and effort into the manuscript.

Additional Resources

Browse our comprehensive list of cheat sheets

References

Brewer, K.M., Harwood, M. L. N., McCann, C. M., Crengle, S. M., & Worrall, L. E. (2014). The Use of Interpretive Description Within Kaupapa Māori Research. Qualitative Health Research, 24(9), 1287–1297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314546002

Church, A.T., & Katigbak, M. S. (2002). Indigenization of psychology in the Philippines. International Journal of Psychology, 37(3), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590143000315

Drawson, A.S., Toombs, E., & Mushquash, C. J. (2017). Indigenous research methods: A systematic review. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2017.8.2.5

Lavallee, L. (2009). Practical Application of an Indigenous Research Framework and Two Qualitative Indigenous Research Methods: Sharing Circles and Anishnaabe Symbol-Based Reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), pp22-40.

Kelly, J. (2008). Moving Forward Together in Aboriginal Women’s Health:

A Participatory Action Research Exploring Knowledge Sharing, Working Together and Addressing Issues Collaboratively in Urban Primary Health Care Settings. Dissertation. Flinders University

Ku Kahakalau (2004). Indigenous Action Research: Bridging Western and Indigenous Research Methodologies. Hulili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being, 1(1).

McCleland, A.(2011). Culturally Safe Nursing Research: Exploring the Use of an Indigenous Research Methodology From an Indigenous Researcher’s Perspective. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(4), 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659611414141

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2013). Towards an Australian Indigenous Women’s Standpoint Theory. A Methodological Tool Australian Feminist Studies, Volume 28(78), Pages 331-347.

Moustakas, C. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. London: Sage.

Pe-Pua. (1989). Pagtatanong-tanong: A cross-cultural research method. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 13(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(89)90003-5

Pe-Pua, & Protacio-Marcelino, E. A. (2000). Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology): A legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00054

Smith, L.T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies : research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Stronach, M.M. & Adair, D. (2014). Dadirri: Using a Philosophical Approach to Research to Build Trust between a Non-Indigenous Researcher and Indigenous Participants. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies, 6(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v6i2.3859

Weber-Pillwax, C. (2004). Indigenous Researchers and Indigenous Research Methods: Cultural Influences or Cultural Determinants of Research Methods, Pimatisiw. A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health 2(1); pp. 77-90.

Yunggirringa, D. & Garnggulkpuy, J. (2007). ‘Yolngu Participatory Action

Research’, paper presented to Moving Forwards Together; Action

Learning and Action Research, Tauondi College, Port Adelaide

https://www.lowitja.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/researchers-guide/43-64-Chapter3.pdf

Frequently Asked Questions

When you start your ethics application it is important that you know exactly what you are going to do – what your research questions are, how you are collecting data, from whom and what you are going to do with the data. So, the best way to start your ethics application is by going through your methods step by step ensuring that you know all bits and pieces that are important to your research so you can talk about them in detail and in layman’s terms for your ethics application.

Check out the Ethics and Research Process pages on this web site and the ethics sheet for more information.

Changes in research approaches are not uncommon. You will need to inform the ethics office at your institution about those changes, though. In most cases, it is sufficient to submit a so-called variation request in which you state the changes to your protocol, and also amend the previously submitted files where necessary. At many institutions this can be done via email, but it is recommended you check with your ethics advisors on how to best proceed as this may depend on the scope of changes.

This is a tricky question and there is not one answer that fits all as a start into a HDR journey depends on where you come from (e.g. industry or university), what you are interested in and if or if not you already know who you want to work with as your supervisory team. If you are from outside the university, but have an idea of what you want to research, it might be best to identify the faculty and school that suits your needs best and get in touch with the respective postgraduate coordinator to see how you can best identify people who can help you.

If you are from within the university, it might be easiest to speak to the lecturers and unit coordinators you have come across and see if they can help you along.

In addition to understanding who your supervisory team might be, it will also make sense to familiarise yourself with the requirements for the HDR journey you are interested in so you know what you will need to deliver.

Also engage with the information on choosing a supervisor and the milestone process.

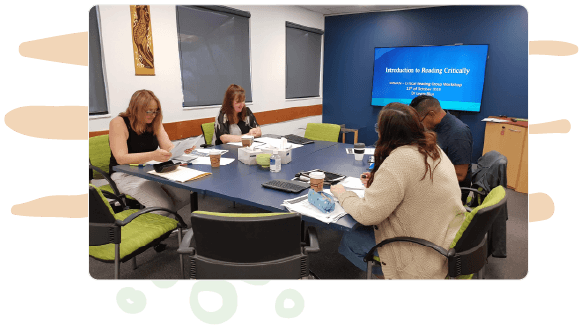

Reading critically and writing academically are two very specialised skills that need ongoing training. Most institutions offer training courses for HDR students for both skill sets. It will be best to check with your library or institution for appropriate workshops.

Also engage with the information sheet on critical reading and academic writing from the web page.

No. While you are very likely going to use a qualitative data collection method when you are engaging in research with Indigenous Communities, it is not appropriate the use a Western model to engage in this kind of research. When researching with Indigenous Communities, you will need to find a methodology and method that are appropriate for the context that you working within.

Explore the pages on Indigenous Research Methodologies and Methods to learn more about appropriate ways in engaging with Indigenous communities.

No. The skills you learn during your HDR journey are very broad-set and are useful and applicable in a number of contexts. For example, public speaking and presenting are important in many industry contexts and so are project management skills. All of these and more are skill you will learn and develop during your HDR journey.

Engage with the section and skill development and career planning to learn more about the skills you will learn.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following web page may contain images and representations of deceased persons.